Prelude Beautiful anchorages on this leg, plus time at docks since gaps in my pre-departure prep have caught up with us. Problem-solving – done with the help and encouragement of many – not only fortify our patience but make this the most satisfying leg of the trip!

Sunday 18 June 2023 – Ell Cove 0800 departure, arrival 1800 N 57º11.9’ W 134º50.9’.

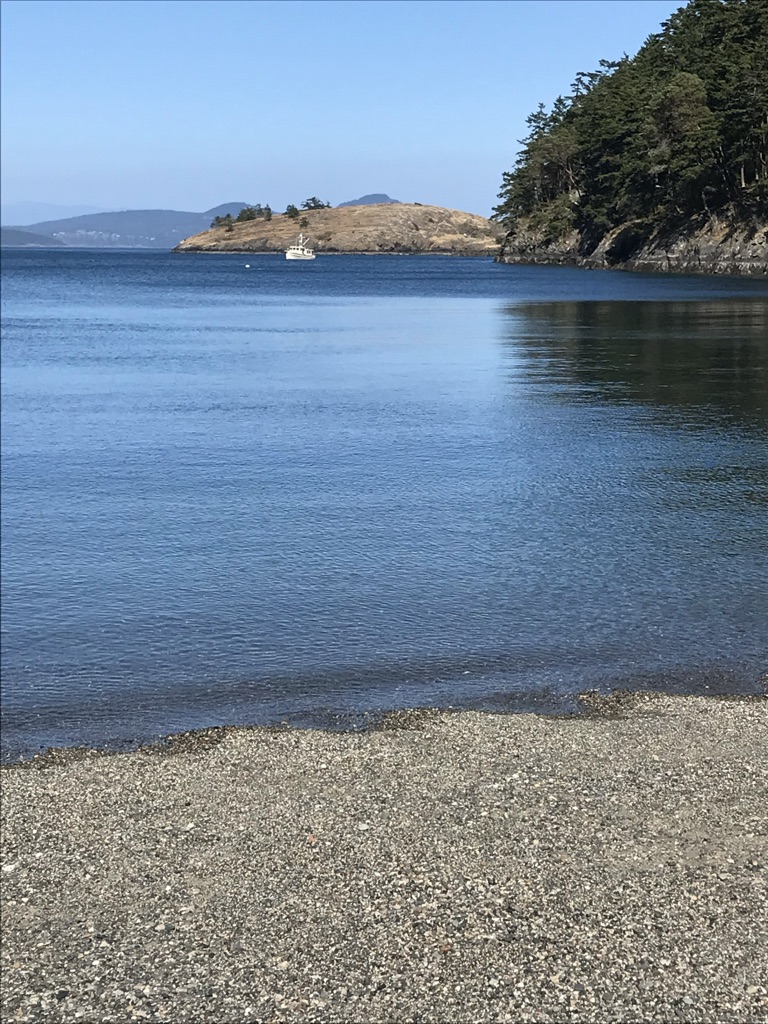

We time our departure to arrive at Sergius Narrows at slack and transit the length of Peril Strait in a day, before tucking into tiny Ell Cove, this year’s discovery. It’s not on our charts but for the spectacular Waterfall Coast of Baranof Island we trust Navionics. More and more each trip.

Kismet is there at anchor when we arrive. Before leaving, on the morning of our rest day, Tom and Michele come by to say hello and catch up on the news. These ebullient Floridians are cruising the Pacific Northwest through September. We’ve been crossing paths since meeting at Devil’s Bath Brewery in Port McNeill in May. The really interesting questions they kept asking persuaded me give up on daily blog writing. Now it’s Tom and Michele who tell us what’s up and where to go.

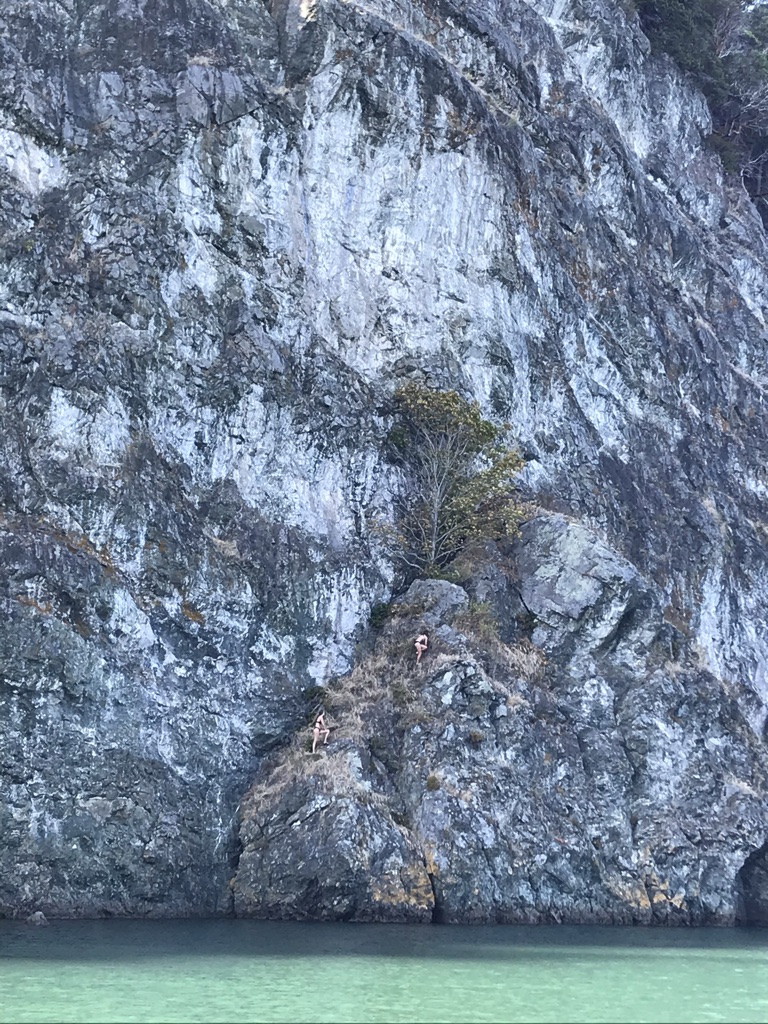

They invite me to hop into their Grady-White dinghy and off we go to the waterfalls, immediately south of Ell Cove. I have no idea how to take a selfie without throwing my phone in the drink, so they do it for me!

Tuesday 20 June 2023 – Ruth Island in Thomas Basin 0845 departure. Pt Gardner calm in good weather and slack current. 1730 arrival at N 56º 56’ W 132º 48’.

What a difference our rounding of Point Gardner is this time! We take it at slack and spend the rest of the day on the big waters of Frederick Sound, remembering the year they were encumbered with dozens of sleeping humpbacks. This time we see none, though the sea otters are back in force.

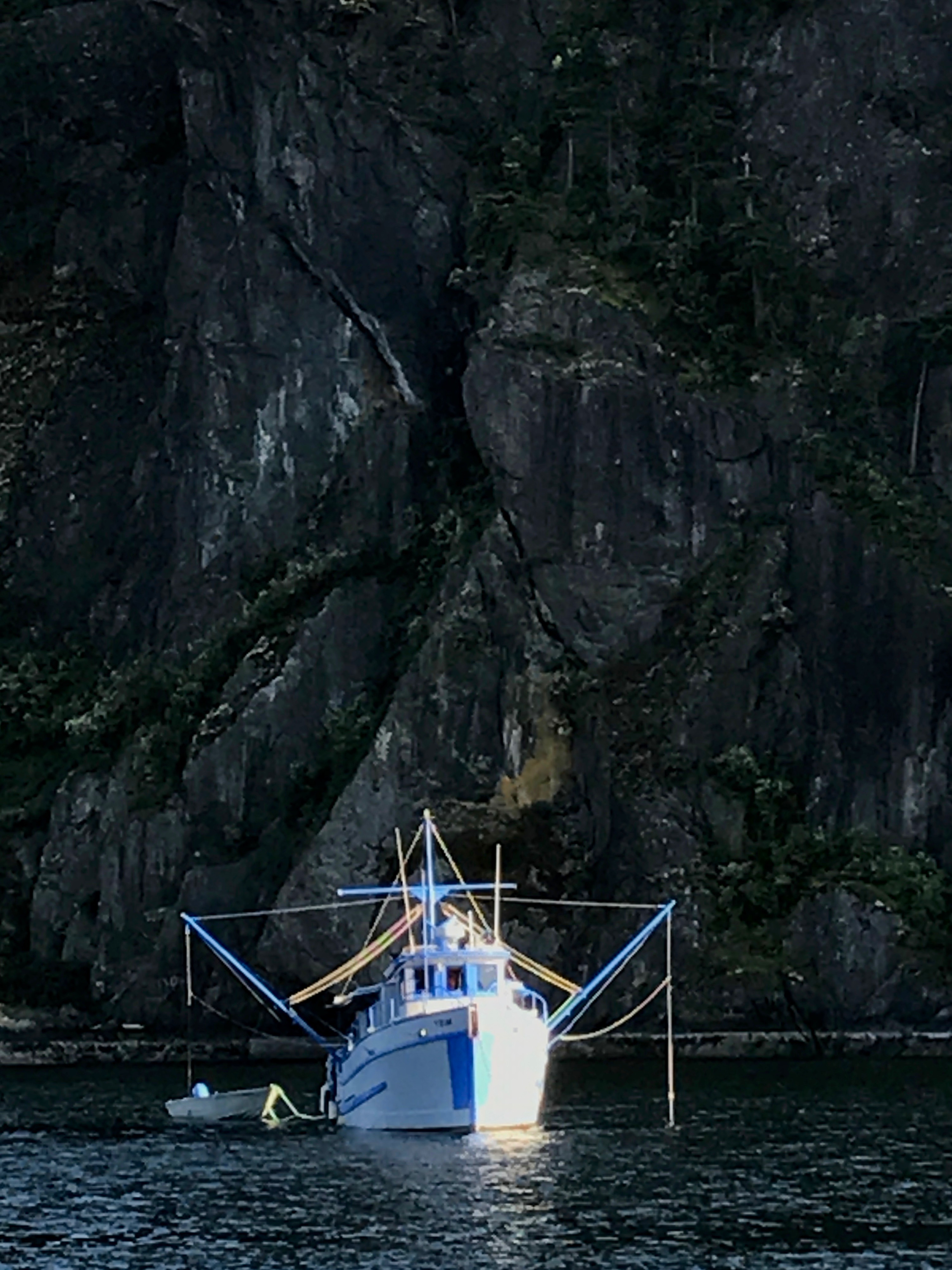

Jack surprises me with a stop in Thomas Bay, which he remembers from a previous trip but which seems completely new to me. We drop anchor behind Ruth Island, which is empty save for forty or so shrimp pots. At the end of a long day, fishermen arrive to pull them, empty the catch, rebait, and drop them again with speed and skill. It’s a dance.

Wednesday 21 June 2023 – Petersburg Departure 0930 to tour Thomas Bay. Arrive at North Harbor 1300. 56° 48.16’ N 132° 56.31’W.

Near the head of Thomas Bay, the Baird Glacier, the water turns turquoise and carries bits of ice. Before it lies a moraine with a large area of glacial outwash, reputed to have a variety of interesting wildlife. It’s hard to get an anchor to hold in glacial waters but with extra crew or a guide, going ashore is feasible.

Interestingly, the southern-most tidewater glacier in the United States is the LeConte Glacier just south of here. Fed by the waters of the Stikine-LeConte Icefield, the clean, blue face of the Le Conte Glacier is actively calving both above and below water. So it’s best visited with an alert and knowlegable guide in a fast, small boat. But alas, we haven’t yet been. Neither north- or southbound have we been able to time our arrival with an available tour out of either Petersburg or Wrangell. In 1900, Petersburg Founder Peter Buschman did well to establish the capital of Little Norway in so close to available ice.

We spend the afternoon on Morning Light watching the comings and goings of fishing boats delivering their catch to Icicle Foods, whose processing operations now boast a large, open, state of the art space in the fresh air high above the docks. Ocean Beauty’s Petersburg Location is still shuttered, with company locations farther north in Kodiak, Cordova and Naknek.

Thursday 22 June 2- 2023 Coffman Cove Departure 0800, arrive 1430 at N 56º 00.6’ W 132º 49.9.

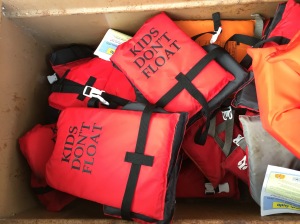

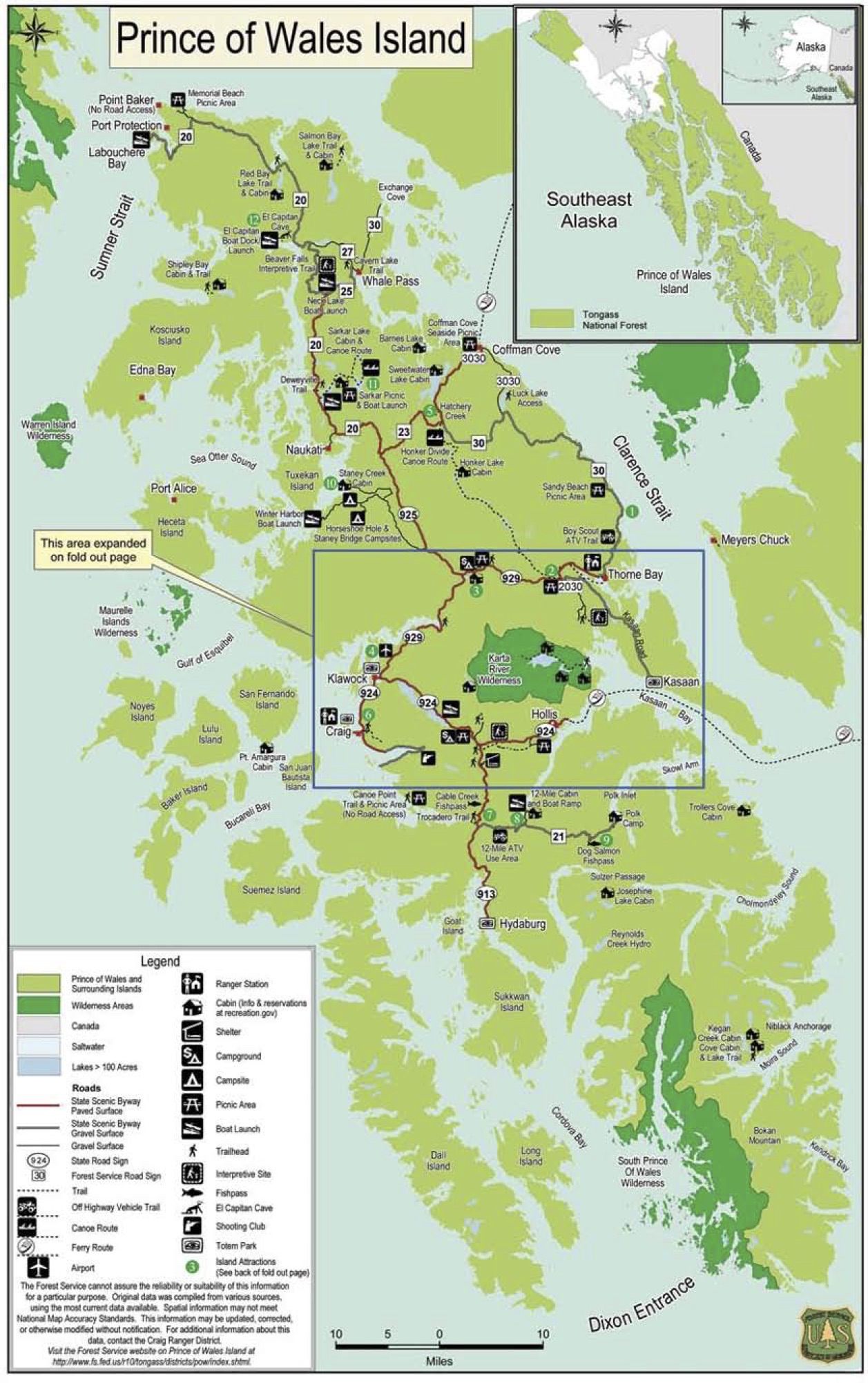

Across Chatham Strait lies Prince of Wales Island, the fourth largest island in the United States, after Puerto Rico. Prince of Wales, or POW. is seldom visited by non-Alaskans, although circumnavigating it is a cruiser’s dream. Among the island’s distinctive settlements is the village of Coffman Cove. It’s a destination for Alaska residents eager to fill their freezers with their annual personal catch. It’s especially popular with Wrangell families who may spend their weekends on the water bouncing around in small boats with a knowledgeable guide. in small boats. They stay in modest lodges or with local people.

On the way, we pass several dozen sea otters, all of whom sit up and watch us pass. And when I pay moorage, the ravens of Coffman Cove check me out at the top of the ramp.

Friday 23 June 2023 – Kasaan Departure 0800, arrival 1515 N 55º32.2’ W 132º 23.9’

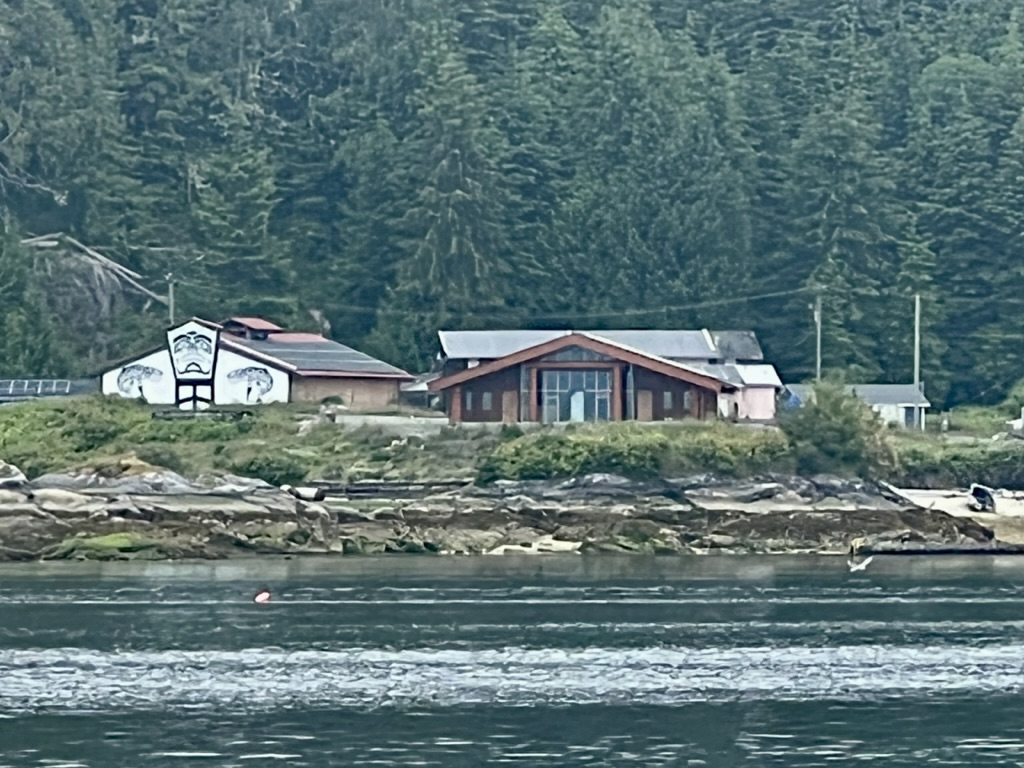

As for distinctive POW settlements and fine welcomes, Kasaan is second to none. Two dugout canoes, a small one for kids and a bigger one, with paddles of all sizes, greet us as we head up the ramp. It’s rained and the canoes could use bailing. However, you don’t touch a ceremonial Native craft without permission.

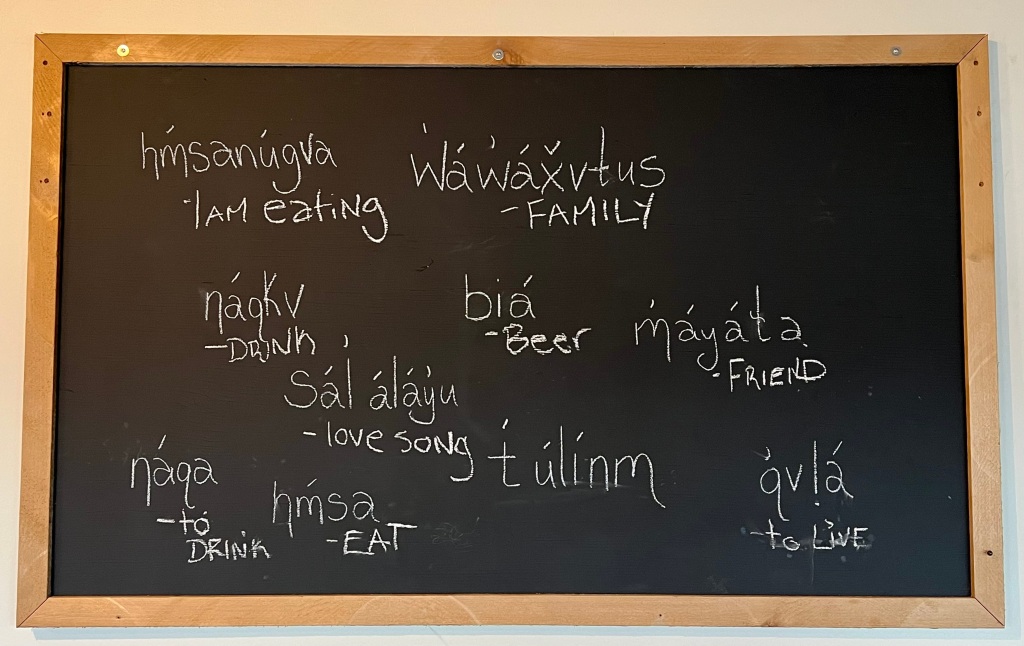

A new stretch of boardwalk takes us along the shore and into this tiny Haida village. No Canadian First Nation and none of their Alaskan tribal members are more boldly rooted on the shores of the North Pacific than the Haidas. For millennia pre-Contact they struck fear and terror into others, traveling in their great canoes to tangle with the likes of the Makah of the Olympic Peninsula and coastal communities to the South.

We look for the carving shed where we spent time with young Master Carver, Stormy Hamar several years ago, when he was managing the building of Whale House deep in the forest beyond Kasaans renowned collection of totem poles.

This time, it’s his son Eric who’s holding down the fort and serves as Watchman, protecting Haida cultural riches. “Of course, you can bail the canoes,” he says, “They’re there to be used. The kids love them.”

In fact, a very hip contingent of hip young Haida appears to have moved into Kasaan. Eric and his wife, who hails from Coffman Cove, have leveraged the village population from 50 to 51, with #52 on the way!

In the clearing between the carving shed and the contemporary long house that now houses the library, stands a new pole, designed by Eric’s father and completed with assistance from other carvers. With the help of the bronze plaque erected nearby, I “read” it. Unpainted, its story is told from bottom to top, the virtuosity of the carvers evident in the three-ply sisal rope which ties the past to the future. It takes my breath away. My photo does it no justice. I can wait for a coffee table book or a traveling exhibition.

The Organized Village of Kasaan is both a place to visit and a place to watch. And now one can zoom in on a village council meeting.

Saturday 24 June 2023 – Ketchikan Departure 0700, arriving N 55º 20.3′ W 131º 38.4’

The Disney ship appears as we approach Gastineau Channel and is securing its lines at Cruise Terminal #1 when we arrive. We slip under its bow and into our stall in Thomas Basin.

From here we can see the Race of Alaska Finish Line and hear the horn. Luckily for us, we’re there for the first of the human-powered competitors. The first rower in is Team Wave Forager‘s Ken Deem of Tacoma. He’s followed on Sunday by Team Solveig with Stina Booth and her brother George from Boise (their 2nd R2AK!)

These finishers join the tiny crowd of diehard R2AK fans who greet each team of incredible athletes Next in is Team of One aka Damon Colbry from Maine, the guy in the picture. He hops onto the float giving nary a clue in his body language that he’s just completed 16 days and 700 miles on the wild waters of the Inside Passage. To say nothing of completing the boat; Damon confesses that he was barely finished building it before the race started.

Race Boss Jesse Weigel is outstanding in his media role. Nothing like being in the presence of these incredible athletes with Jesse asking penetrating questions about strategies, surprises, low points, and high points. The four from the three teams all know one another, are middle-aged, and have done the R2AK or stuff like it before. Need inspiration? Hang out a couple of weeks at the Race to Alaska Finish Line.

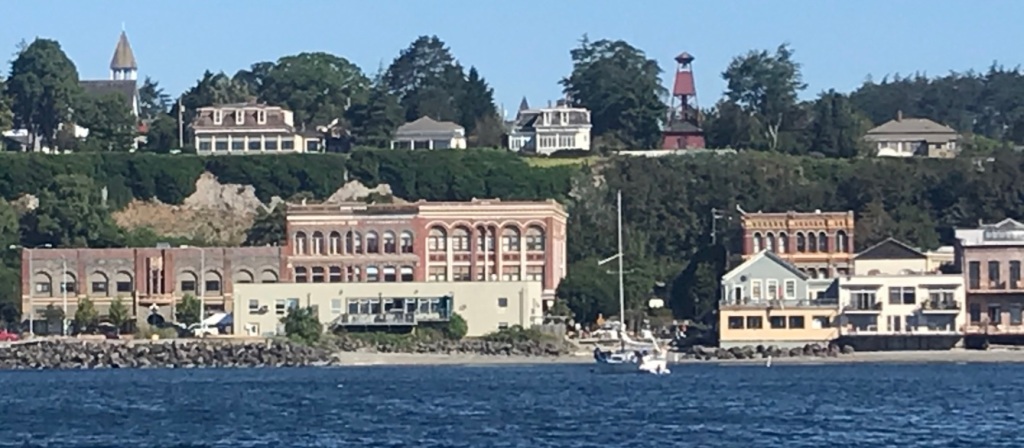

In the late afternoon as the big ships pull out, we walk around Ketchikan’s historic waterfront. The City Museum has taken the place of the old library, Ar Parnassus Books we run into Ray Troll. Then drinks at the Elks Club on Creek Street.

Monday 26 June 2023 – Foggy Bay Departure 0700, arrival 1030 at N 54º56.9’ W 131º41’

When you’re crossing Dixon Entrance, how do you know when you’ve crossed the border? Well, check the light stations along the way.

What on earth is that Moroccan mosque doing on that roadless shore? Well, that’s what a lighthouse in the southernmost parts of Southeast Alaska looks like. These were built during the New Deal, when public buildings suddenly were infused with all sorts of creative design. Art Deco continued to draw on Moorish Architecture and the solid North African minaret fit the bill for Alaska’s stormy shores. Five Finger Light near Petersburg is one you can visit. You can even volunteer as the lighthouse keeper.

When see a cluster of white buildings with red roofs and the Maple Leave flag unfurled among them, you’re in Canada. Green Island (below) is the first one we pass southbound.

Many of Canada’s light stations are manned, with some boasting helicopters with rescue teams. An illustrated list of BC coastal facilities is here and photos of the light towers on the Pacific Coast and on inland lakes is here. Not all BC lights are pretty. Holland Rock near Prince Rupert is an ugly tower on an ugly rock and the Sand Heads Light is built on pylons far offshore to mark the channel of the Fraser River. As unsightly as these two are, I am grateful for the people who maintain them and show us the way.

Tuesday 27 June – Prince Rupert Departure 0530 AK time, arrival 1300 PDT. N 54º 19.2’ W130º19.2‘

As soon as we pick up a phone signal, I call Prince Rupert to see about moorage. The first reservation of our trip gets us a place on the rocky outside of the guest dock.

On arrival we take on water and take off recycling and trash. Then we head to the Museum Store, Safeway, and BC Liquors, before sitting down to a meal at Breaker’s Pub. Safeway offers two free deliveries daily so we watch our groceries arrive at the top of the ramp.

Thursday 29 June 2023 – Baker Inlet Departure 0515, arrival 1115 N 53º48.7’ W 129º51.3’

Baker Inlet is spectacular! This is our first time here. The curvy, blind, narrow entrance is tricky and is best done at slack. It’s easier the get the timing right on southbound passage from Prince Rupert.

While I lounge, Jack works out in his bungie cord gym in the cockpit. Daisies are our wedding flower, thanks to whoever picked them on the way to City Hall 52 summers ago. These are from Coffman Cove where daisies proliferate.

Saturday 1 July 2023 Khutze Inlet Departure 0615. Arrival 1615. N 53º.05.3’ W 128º31.2’

Canada Day. We call the Kitasoo Watchman to ask permission to drop anchor on Green Spit, not far from his yurt. He welcomes us from Klemtu, the First Nation village. It’s Canada Day.

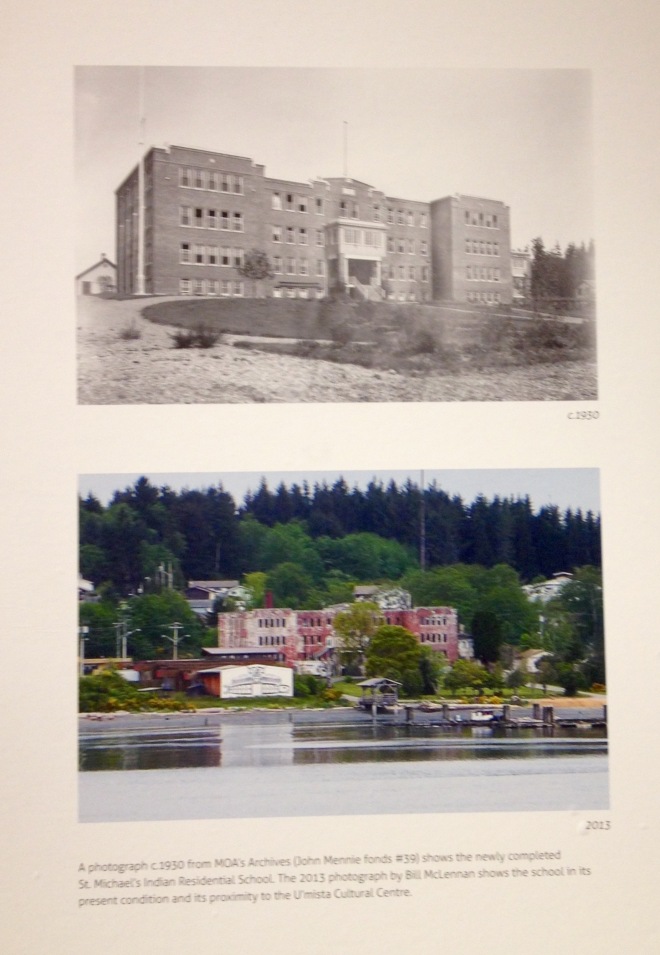

A day off lets me finish the book I bought in Prince Rupert at the fine bookstore at the Museum. Indigenous Relations: Insights, Tips and Suggestions to Make Reconciliation a Reality is by Chief Bob Joseph and his spouse. These management consultants cover misunderstandings that can derail negotiations between First Nations leaders and Canadian executives as the former purchase or arrange for the transfer of assets from the latter. It’s for everybody, however, and will remain in our onboard library.

We’re at anchor for days. There’s no choice, no chance to plug in. Alternator problems begin. When we turn on the ignition to depart, nothing happens so we turn on the genset and take off.

Sunday 2 July 2023 Rescue Bay Departure 0600. Arrival 1200. N 52º30.9, W 128º.17.3’

Right now our house batteries are not charging. Today we are in big waters. To save power, we’ve turned off the communications, apart from our VHF handhelds. The three-day holiday weekend feels like a repeat of the Victoria Day long weekend when left Port Neville after a rocky night at anchor out of snotty weather. (Port Neville’s is no longer a pioneer settlement but has reverted to a simple geography, a broad windy inlet named by George Vancouver.)

We are thankful for perfect weather and the fact that we’re finally below the 53rd parallel. Jack says the 53rd is the reality that no one talks about. It’s where weather patterns change and after sailing north into winter, we’re headed south into summer.

Then the generator that has provided the necessary amps goes silent. Oscar Channel seems a safer bet that narrow, rocky Jackson Pass.

Heading north to Rescue Cove, we pass a couple in a canoe weighed down with provisions and gear under a red cover. After lunch, the canoe appears, the man using a single paddle, the woman a kayak paddle. Everything is taken out to dry on the beach. Later I look and they’re gone! Then in the morning, canoe and gear emerge from their camp and they paddle off, leaving us behind.

Alas, the engine will not turn over. My efforts to jump the starter battery from the house and gensite batteries fail. Cables are not long enough to reach the bow battery that powers the windlass. We’re stuck. Good weather. Safe place. Fresh food. No hurry.

Jack calls on the radio for assistance placing a ship-to-shore call. Somebody in Bella Bella or Shearwater can provide a tow. Or maybe there’s a boat around. The Coast Guard puts out a standard a call for assistance. Forever Friday out of Bellingham, within 30 minutes of leaving the anchorage, returns. We hadn’t thought to ask them for help. Randy wrestles the battery from their dinghy onto Morning Light, but that doesn’t do the trick either. The dispatcher checks in for an update. Ten minutes the Coast Guard calls back saying their ship will arrive in two hours. What? Okay. I put out the fenders and read my book.

We’ve got fenders out on both sides. Cape Farewell appears suddenly on port and ties us up. The large crew of eight is all business. Captain Brian directs everyone to their stations. The ship’s engineer and a young trainee step on board. “Just relax, nothing for you to do, and you don’t pay a cent,” says Karen, as sets about showing her trainee – and us – how to secure the propeller shaft with a large pipe wrench. We remember one that size on Aurora. Not understanding its use, we left it on board, so that wrench is now cruising the Caribbean. To protect the shaft to keep it from turning and to secure the wrench, I supply a bit of bike inner tube and the needed length of line and it’s done.

Karen is a star. She runs us through the trouble-shooting basics and most everything checks out. Then we take a look at the spares. Oops. It looks like my assumption that we’ve got an impeller for the generator is wrong. A glitch so elemental! I’m ashamed.

I fix sandwiches and the three of us chat about her retirement plans. I ask about large Coast Guard crew on the Cape Farewater and learn they have neither a galley nor a head. Oh, those poor women!

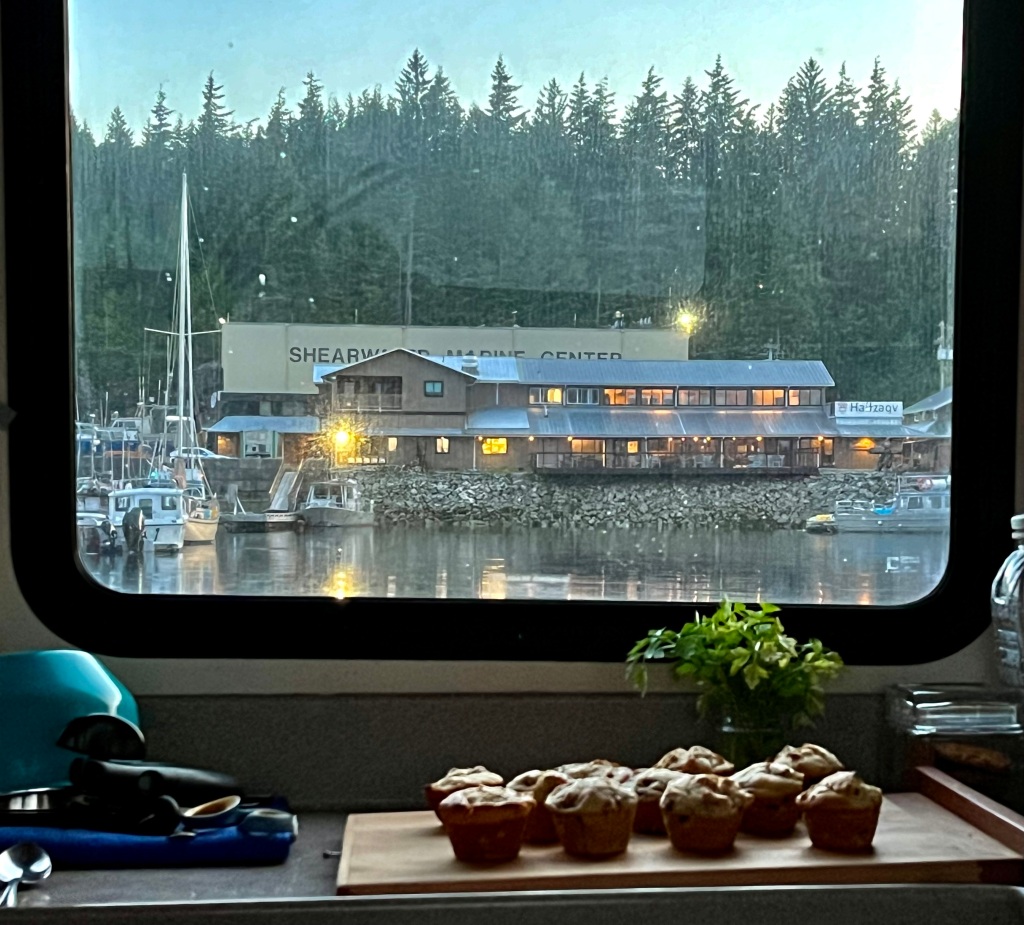

Monday 3 July 2023 Shearwater Departure 1000 under tow from Coast Guard. Arrival Shearwater 1700. 52º08.8 N 128º 05.3 W

“Good to see you again!” says Masha greeting us on arrival. There’s a pot luck right here tonight. She’s the owner of the 42’ double-ender Harmony, which joined us on the guest float in Sitka. I learn she is half Croatian and purchased the boat – which obviously needs work – within the past year. She grew up sailing, lives aboard, and can certainly do it. In Shearwater, the young man with her flies off somewhere, and Sam, who was her crew in Sitka, comes back aboard. Masha is into seaweed. I break out a bottle of Foraged and Found smoked seaweed salsa. We agree that the plans and products of this new woman-owned Alaskan company are promising.

After supper on Morning Light, I join the potluck. Our leftover guac joins the papaya cubes I’d left on the table earlier. Self-ripening fruits save time and trouble. The fine mix of locals and cruisers include two old guys and a young German who hove two for two nights off Yukatat after being abandoned by their captain, but I never get the whole story on that. Jean Marc dinghies in from across the bay with a salad of baby kale, fresh zucchini and and chopped herbed veggies from his garden. The leftovers will be our next meal. Local resident and tugboat crew member Patricia, tells us that Christophe – the harbormaster from way back – is back. No longer trying to salvage Butedale, still pilots a coastal tug and tow, and has become a ship surveyor. I’m too busy to track him down and it’s sad to see him pull out in his black-hulled sailboat with trolling poles.

It’s a bit discouraging to have neighboring boats depart every morning. The couple crewing S/V Windrose M are flying an orange shirt! I ask them how the see the progress of Truth & Reconciliation. Truth is going well, they say. Reconciliation will be much harder. And yes there’s quite a bit of redneck intolerance in North BC as First Nations take charge of Conservancies in their territories and buy up white businesses as they come up for sale.

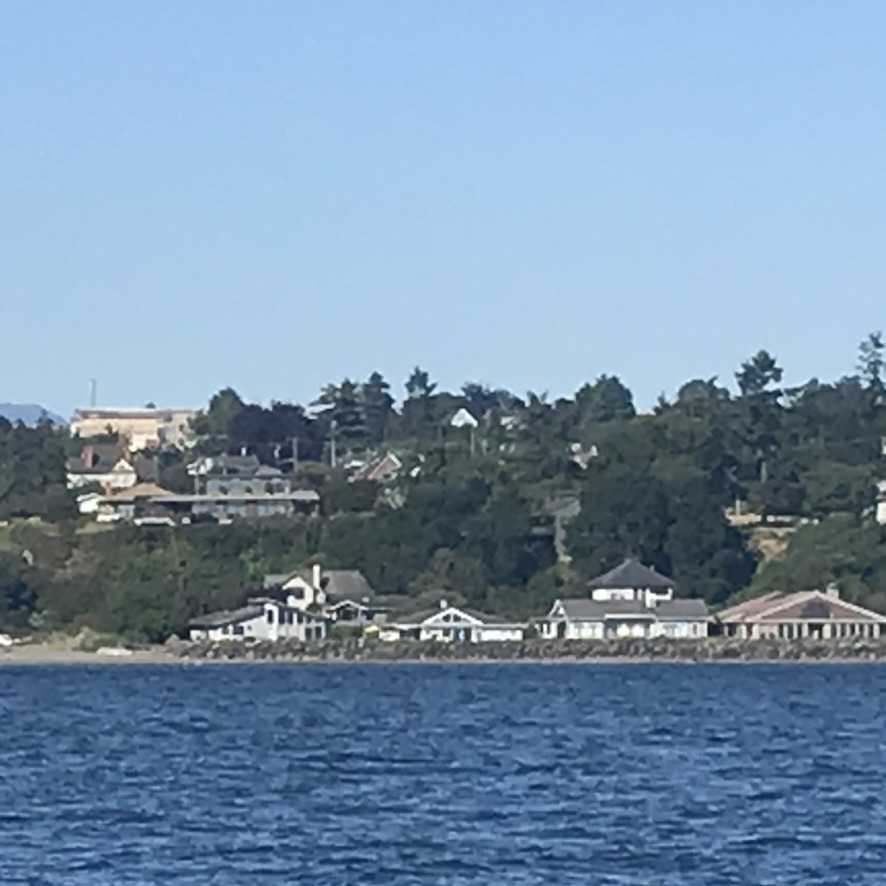

Opposite us on our last day is the crew of S/V Tatoosh out of Nanaimo, They agree that the modern look of the Nanaimo waterfront is cool and will stand the test of time. They explain how the island with the tower was incorporated into the plan, linking the large ship docks with the floats serving the fishing fleet and recreational boats.

M/V Lemon Drop, one of the small, out-boarded Ranger Tugs we first encounter in Fury Bay, is buddy boating with Channel Surfing. So named, the Jack and Jill crew tell me, after realizing that it was time to abandon sedentary channel surfing habits. Lemon Drop is skippered by an attractive woman who tells me she 76 and asks me how old I am. Instant respect as these are the tiniest US cruising boats we encounter all trip.

In contrast, is the 90-foot aspiring super yacht rescued from foreclosure by retired Alaskan hoteliers Mark and Mary, who operate it double-handed! They add crew when it’s chartered, which is easy with weekly rates for such a vessel running above $50K.

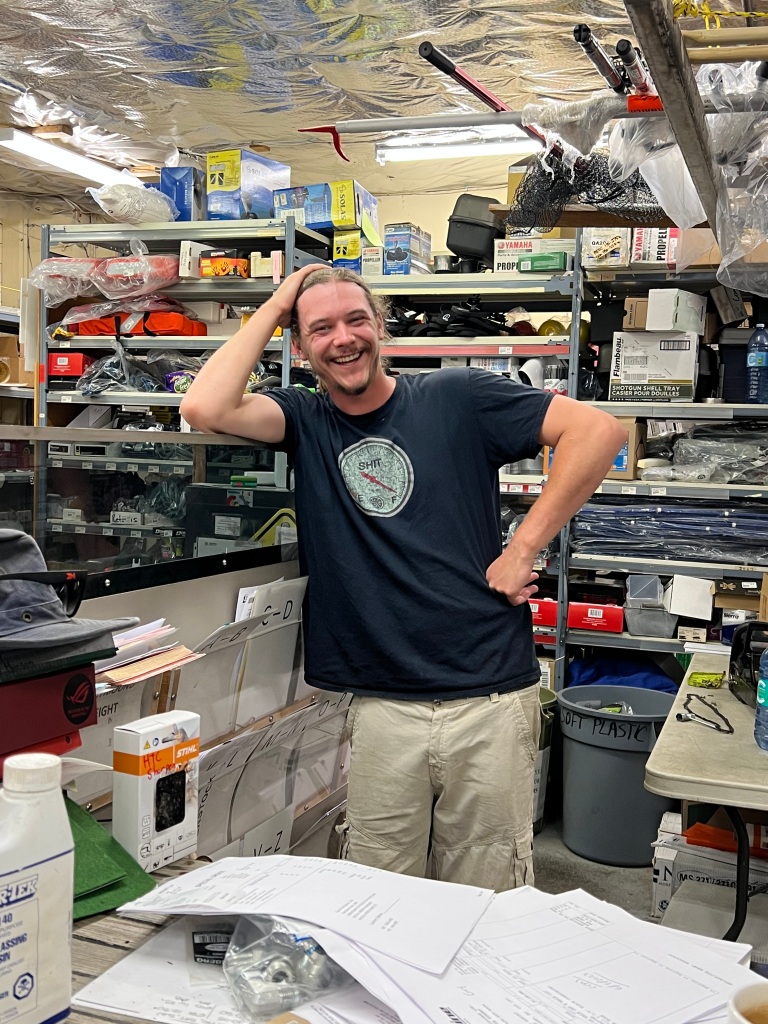

I’m getting to know the local people, a good mix of young and old, of indigenous and not. The Hieltsuk seem grateful when I express sympathy regarding the loss of their elder. Everyday, I chat with Maureen who works in the shipyard front office, assisted by Acacia. Maureen’s husband, Jay, works on the sports fishing side of the business. Tony, John, and Zack are at the Marine Store. The young clerk at the Grocery Store is Stun, a Hindu Indian, who immigrated recently all by himself.

One day after lunch in the restaurant, Karen appears with Jean in tow. They ask how things are going. I tell them all we’ve learned from various people pending the arrival of a new impeller as well as frustration with service gaps, since Shearwater Marine’s lead mechanic is on vacation. Jean wonders if Nate Axel might help, if he’s not out on the water in charge of the engine room of a big fishing vessel. She calls him then and there. He comes, climbs into the engine room, and declares the alternator dead. So what about just using the generator to stay charged up during the long string of anchorages ahead? That should work, he says. As does everyone else. And if that fails, Jack has just bought longer and better quality jumping cables so we can pull juice from batteries in the bow and stern.

About 100 people live in Shearwater on Denny Island across the water from the Heiltsuk First Nation town of Bella Bella on Campbell Island. Water taxis link the two with regular service from early morning to late at night.

Zack – that’s him in the photos – says the impellers are expected Thursday or Friday on the regularly scheduled flight that arrives in Bella Bella about 3 pm. Nothing on Thursday. Then nothing on Friday when the SeaBus delivers. Zack calls. Taxi guy will fetch tomorrow. Expect by noon. Tomorrow comes. Funeral day. Still nothing.

I track down Zack – his day off – and ask permission to take over the assignment. He insists it’s his job and is back on it. Hops on the SeaBus. The first rain in a month falls. Turns out taxis are not running. Zack sprints to the airport and delivers the impellers to Morning Light at 3:30 pm. First miracle. Zack is a star! The second is I install the impeller, replace the hoses, and the genset is working again by 5 pm. I’m a wreck.

Sunday 9 July 2023 – Millbrook Cove, Blackney Channel Departure 0510. Arrival 1300. 51º19.6’ N, 127º 44.2’ W.

The genset purrs like a cat. It’s the smoothest passage ever. We’d gotten so used to stopping Fury Cove that Millbrook Cove off Smith Sound was not on our radar. A bit confusing to enter – we found the single red buoy only upon leaving. Do Garmin, Navionics, or our old charts locate it correctly? If one does, the others don’t. The Navionics apps on our two iPads almost always agree and are getting more accurate every year.

Monday 10 July 2023 – Port McNeill Departure 0515, Arrival 0100 50º 35.7’ N, 127º05.3’W

Ah, Port McNeill. It’s a place where people know how to do stuff, where skilled hands willingly pass on skills, and where locals seem committed to sustaining the economy of the past into the future. They have a lot to keep going: fishing, logging, and mining industries plus the minutiae of contemporary life. Complement a mechanic – are they still all men here? – and you’ll likely get a modest reply: “Well, I’ve been doing this since I was eight.”

At 10 am Randy of Aussie Marine appears at our boat, cheering us with his presence and demeanor, asking questions, peppering technical talk with good stories, as he removes the alternator. “Let me take this to my neighbor,” he says, explaining that he’s an old guy who works out of his home.

By 2 pm Randy has had the alternator diagnosed, equipped with a new brush to replace the broken one, and reinstalled on Morning Light. Who knew such a thing was possible?